On 5 March 1914, The London Group held its inaugural exhibition at the Goupil Gallery, 5 Regent Street, London. You probably haven’t heard of the Goupil, which shifted between several central London locations before it was flattened by a German bomb in 1941. Despite a nomadic existence, The London Group has proved much more durable: it survived the Second World War, decades of changing tastes in the art world and a verbal carpet bombing by bilious art critic Brian Sewell. Dr Richard Cork, Sewell’s predecessor at the London Evening Standard, was much more complimentary when he spoke at a reception at Tate Britain on the 100th anniversary of that first exhibition.

An invitation to an after-hours event at a major London gallery is always exciting. With fewer people around it’s easier to absorb the impact of Caruso St John’s high-profile £45 million makeover of Tate Britain. Entering through the reopened “front door” on the Millbank side, I descended via the stunning new spiral staircase beneath the rotunda, to the pristine white surroundings of the cavern-like Djanogly café, where the reception was held.

Current members, their partners and invited guests heard Richard Cork reflect on The London Group’s early years. It was an era in which the art world was dominated by “isms” (Fauvism, Cubism, Vorticism), and the challenge of conveying wholesale slaughter on the battlefields was taken up by many painters and sculptors. They included David Bomberg, who was part of the Group’s first exhibition and whose painting, In The Hold, was a key work in last year’s A Crisis of Brilliance exhibition at the Dulwich Picture Gallery.

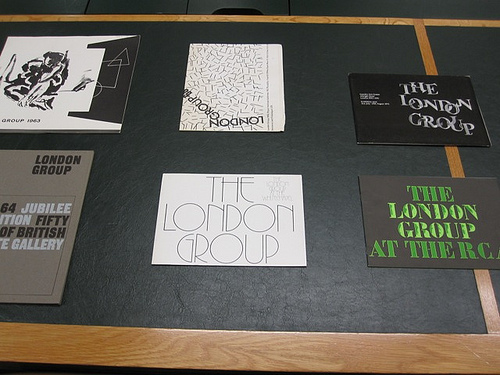

A selection of catalogues from London Group exhibitions, held in the archives at

Tate Britain (pic Tom Scase).

As Cork touched on some of the controversies and described the brutal evolution of Jacob Epstein’s Rock Drill sculpture, I thought about a more recent attempt at emasculation. Brian Sewell’s withering assessment of the exhibition, Uproar! The First 50 Years of The London Group 1913-1963, included the assertion that the Group has been in “irreversible decline” since the end of the Second World War and “ought long ago to have been put down”. Strong stuff. I might be reading too much into the rantings of a grumpy old man, but it sounded as though Brian thought The London Group should have perished in a Luftwaffe bombing raid.

I’m not a professional artist or art critic; I was flattered to be invited to the Tate reception as a result of a blog I wrote last year. Brian Sewell is much better qualified than I am to compare the merit and the impact of The London Group’s second half century with its early years at the cutting edge of the art scene. The first London Group show featured more than 100 works by artists including Wyndham Lewis, David Bomberg and CRW Nevinson. It’s probably too early to say whether any of the current members will be as influential – though Dame Paula Rego’s international reputation precedes her.

But Sewell’s comment that The London Group in its later years “has meant very little to working artists and nothing at all to the wider public” is breathtakingly arrogant and ill-informed. Did he bother to interview any current members before reaching this conclusion? Speaking to them last night and at previous exhibitions, I know that what Sewell dismisses as a “pathetic” Collective is an integral part of their professional lives.

Fortunately, Brenda Emmanus took a more measured approach in this week’s BBC London piece about the The London Group On London exhibition, which continues at the Cello Factory until 12 March. Among the interviewees was 91-year-old Albert Irvin RA, a member since 1965, whose paintings and prints are most often characterised as “exuberant”. (That’s not a description that could ever be applied to Brian Sewell.)

Longevity is not always a reliable guide to the value of work, organisations or individuals. (A certain veteran art critic should have been put out to pasture some years ago.) But enduring links to a pivotal era in 20th-century British art are worth celebrating. Tate Britain holds a fascinating collection of London Group documents, catalogues and photos within its huge (entirely dust-free!) archives.

In the words of its current President, Susan Haire, “The London Group is thriving and we expect to be around for the next 100 years.”

www.thelondongroup.com

April 23, 2014 at 5:07 pm

Dear Susan

Tommy Seaward sent me the link to your article on the London Group Tate Reception. As editor of The London Group newsletter I wonder whether you would agree to an edited version of your blog being included in the forthcoming newsletter? I could send you the version if you might consider this. We would like to include it if possible in the May newsletter. Would be grateful for your email address.

Many thanks

Annie Johns