Critics like to bang on about the sex scenes and nudity in the films of Nicolas Roeg. But let’s not forget the bold casting choices that saw old “rubber lips” Mick Jagger playing a louche gangster in Performance and the angelic-voiced Art Garfunkel turning nasty in Bad Timing. In between those films, Roeg made the weird and wonderful The Man Who Fell to Earth starring the chameleon-like David Bowie.

When I was at school the cool kids liked Bowie or Jagger; the rest of us squabbled over the merits of David Cassidy and Donny Osmond. I regret to say that the release of ABBA: the Movie the following year made more of an impression on me than Bowie’s startling debut as a leading man in the spring of 1976. He plays Thomas Jerome Newton, a traveller from the planet Anthea, who comes to Earth in search of water to save his dying planet. After plunging into a picturesque lake outside Haneyville, he stumbles around trying to acclimatise himself to a land that is fertile, yet spiritually arid.

Compare the beguiling opening sequence of The Man Who Fell to Earth with Arnold Schwarzenegger’s smash and grab clothing raid on an LA biker bar at the beginning of Terminator 2: Judgment Day. Newton’s urgent mission requires him to get his hands on some quick cash, so he sells his wife’s ring. “Twenty dollars — take it or leave it” says the hatchet-faced old woman who provides him with a first chastening experience of US commerce. A short time later we see him counting a big wad of dollar bills. I’m guessing he used guile rather than Arnie-style negotiating tactics.

It’s just the first of many gaps in the narrative of a film that’s brimming with ideas, but doesn’t often feel the need to pull them together into a coherent plot. So armed with nine original patents and assisted by lawyer Oliver Farnsworth (Buck Henry), Newton rapidly establishes a business empire that generates billions of dollars but, frustratingly, fails to solve his water problem. Along the way he falls into the clutches of the emotionally needy Mary-Lou (Candy Clark) and piques the interest of ambitious scientist Bryce (Rip Torn). He becomes disillusioned and even dissolute, but he doesn’t grow old. If only he’d stuck to imbibing H20 and stayed off the gin and tonic.

I haven’t read Walter Tevis’s sci-fi novel, so I don’t know how much of what follows is a product of screenwriter Paul Mayersberg’s imagination. Mayersberg, who later co-wrote Roeg’s Eureka and Bowie’s Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence injects plenty of dry humour into the first half of the film. Farnsworth’s comment about how his old life “went straight out the window” is cruelly ironic, considering his spectacular death by defenestration. The visitor’s intellectual prowess is slightly undermined by his naiveté about money and his social awkwardness. But though Farnsworth comments that Newton is “not so very different”, we’ve just had an intriguing close-up of the mismatched pupils that hint at something not-so-human under the surface.

In some respects Newton’s rise and fall is a classic cautionary tale. An outsider with truly innovative ideas founds a business empire, and is then ruthlessly crushed by corporate America when he tries to harness that wealth for his space programme. “This is modern America and we’re going to keep it that way.” As he tunes into a brain-numbing diet of 12 different TV channels at the same time it’s no wonder Newton loses his grip on reality — whatever that is. I would call it information overload, but the bemused spaceman soon figures out the difference between a medium that merely “shows” you everything as opposed to telling you something. The besotted Mary-Lou screams for answers and ends up with a lot more reality than she can handle.

The Man Who Fell to Earth loses its way badly in the second half, as we measure the passing of years solely by the greying hair and increasing girth of the supporting cast. (Candy Clark’s ageing make-up is particularly unconvincing.) As Newton’s exile continues there are frequent jarring flashbacks to the wife and kids back home. Perhaps it’s too many years of watching The X-Files, but I felt these sequences had dated badly and the pathos was somewhat lost on me.

Forget the much-discussed sex ‘n’ dressing sequence in Don’t Look Now, this film contains several scenes that showcase nudity and some truly bizarre juxtapositions. Early in the film Newton watches some traditional swordplay in a Japanese restaurant as Bryce and his girlfriend indulge in one of those apartment-trashing bouts of copulation. They photograph themselves, too. The music, the shrieking and Graeme Clifford’s editing combine to create something that’s more disorienting than erotic. Later, Newton and Mary-Lou explore some inadvisable gun-play as foreplay and there’s also the unforgettable sight of her caressing his naked alien form.

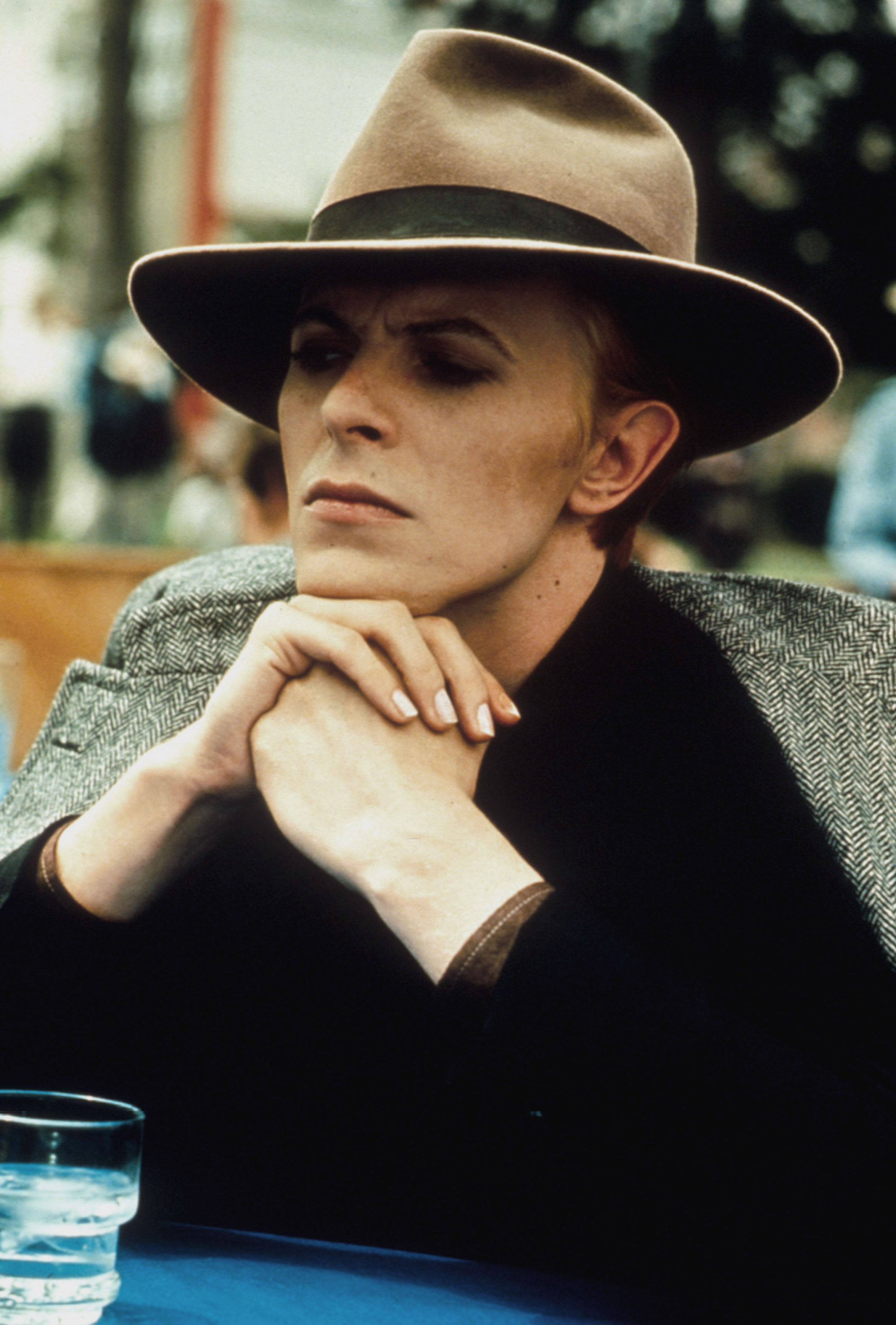

Whatever the stylistic excesses, Bowie’s extraordinary performance keeps you watching. You literally can’t keep your eyes off that languid figure, whose androgynous looks and ethereal presence are perfectly suited to his otherworldly role. Though he doesn’t age like the people around him, his suffering and physical deterioration are, at times, hard to watch. It could have felt like an over-extended rock video, but in Roeg and Bowie The Man Who Fell to Earth has found the perfect combination of directorial flair and old-fashioned charisma.

June 4, 2011 at 7:41 am

do you know what movie was showing on one of the TVs. it featured stacy keach and another man fighting.

June 4, 2011 at 12:09 pm

Hi. I think the Keach movie you’re referring to may be End of the Road (1970), also starring James Earl Jones.