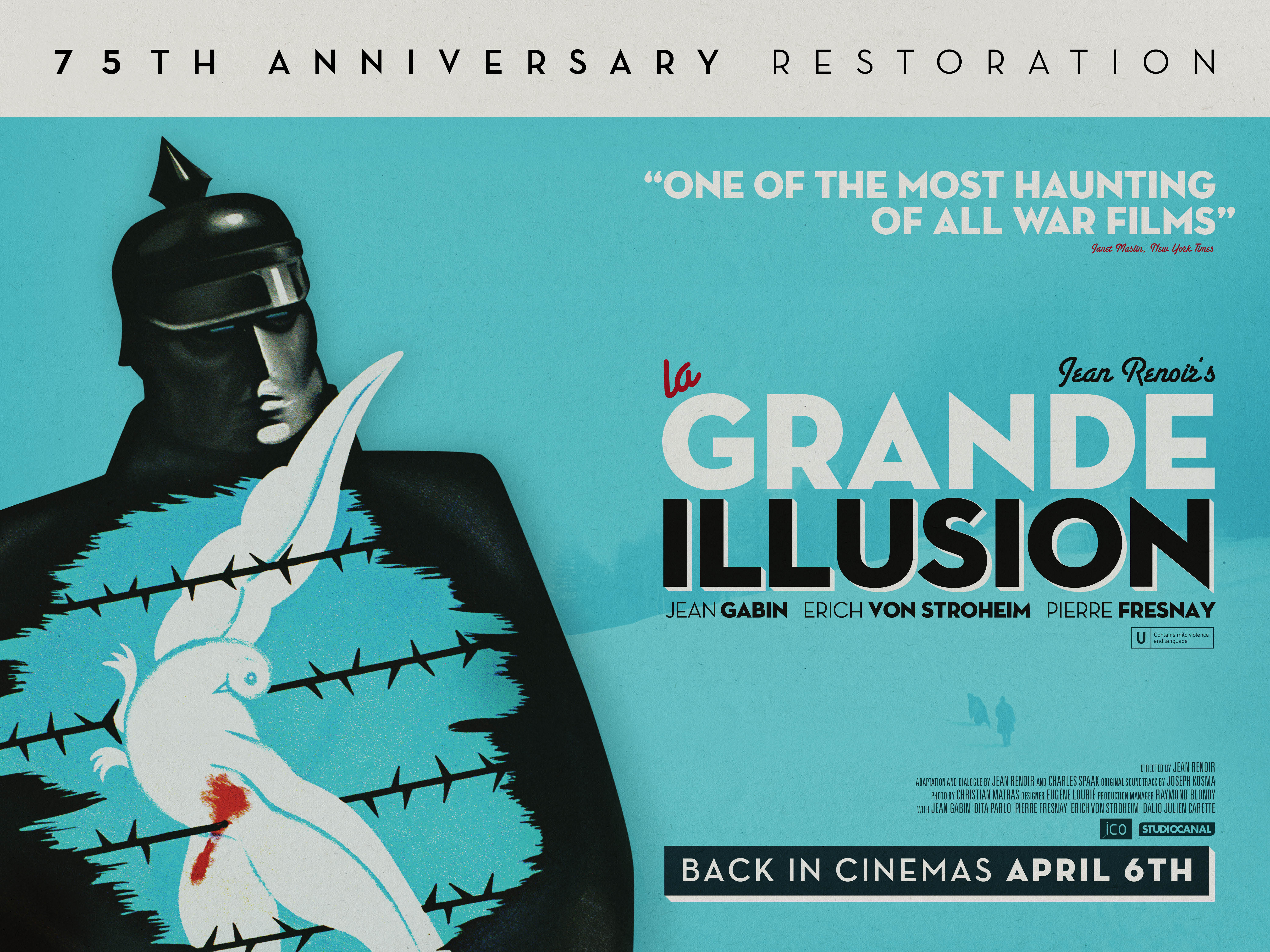

La Grande Illusion celebrates its 75th anniversary this year, but Jean Renoir’s First World War drama isn’t really showing its age. The digitally restored DVD I watched was refreshingly free of all the snap, crackle and pop I used to associate with films from the 1930s. But this story also feels very contemporary in the way it combines PoW drama and romance with a meditation on the humanity rather than the mechanics of warfare. It’s also brilliantly acted and infused with a wry humour.

You could think of La Grande Illusion as a forerunner to The Great Escape. Instead of Steve McQueen, we have the dashing Jean Gabin as fighter pilot Lt Maréchal, who is captured with his fellow officer, the patrician Captain de Boeldieu (Pierre Fresnay). As de Boeldieu prepares for their fateful mission, he’s offered a choice between a flying suit and a jacket: “I don’t mind. One smells, the other moults.”

Soon after, the two Frenchmen are cordially invited to lunch with von Rauffenstein (Erich von Stroheim), the courteous German commandant who’s just shot them down. In an extraordinary opening sequence, Renoir cuts from the cosy interior of the French mess, to the almost-as-convivial atmosphere of the German counterpart. There are no snarling villains here — just brothers in arms who are eager to pull up a chair or help the winged Maréchal to cut up his meat.

If all this sounds a bit like a satire, or even Carry on up the Kaiser, it isn’t. But the script, co-written by Renoir and Charles Spaak, seems determined to sidestep the usual clichés of antiwar films — brutality, pathos and earnest speeches about the futility of slaughter. Instead, his comments on the class structure are revealed through the interactions of a group of likeable and well-drawn characters, framed within a beautifully constructed three-act drama.

The first section sees Maréchal and de Boeldieu incarcerated in the camp at Hallbach. The regime is strict but fair and the day-to-day tedium is relieved by comic moments and acts of kindness. So the German guards ruefully contemplate their meagre lunch, jesting that the Brits are probably tucking into plum pudding. The French detainees enjoy the hospitality of Jewish financier and gourmet Rosenthal (Marcel Dalio), while actor Cartier (Julien Carette) organises the concert party that’s almost obligatory for a PoW film.

Several months and many escape attempts later, Maréchal, Rosenthal and de Boeldieu are reunited at the seemingly impregnable fortress of Wintersborn. Their “host”, von Rauffenstein, obviously welcomes the return of the monocled de Boeldieu, who shares both his world view and his fetish for pristine white gloves.

Von Stroheim was a distinguished writer and director, whose rather forbidding appearance makes his subtle performance here all the more remarkable. Unlike the martinet played by Otto Preminger in Stalag 17, von Rauffenstein is totally sincere when he declares, “May the earth lie gently on our gallant enemy.” Fresnay brings a lightness of touch to de Boeldieu, masking his heroism with a veneer of aristocratic sophistication. Both officers recognise that the old order is collapsing around them — regardless of the outcome of the war.

The undoubted star of La Grande Illusion is Jean Gabin, one of the greatest actors in French cinema, thanks to his work with directors like Renoir, Marcel Carné and René Clément. Maréchal, an engineer by profession, is a low-key presence in the early part of the film. Gabin plays him as the scruffy, romantic everyman figure — the opposite of self-confessed “realist” de Boeldieu. But the calculating de Boeldieu is much better at seeing the big picture, which is why he sacrifices himself to facilitate a daring escape.

After the PoW drama and then the “bromance” between von Rauffenstein and de Boeldieu, Renoir gives us a touching finale as Maréchal and Rosenthal go on the run. Maréchal falls for the German widow (played by Dita Parlo) who is sheltering them at her farm, and his meaningful looks soon overcome any communication difficulties. Perhaps this section of the film is a little saccharine, compared with what’s gone before. But the jaunty score and lovely Alpine scenery point the way towards a hopeful future.

If this film had been made ten years later, when Europe was still blighted by the horrors of Nazi Germany, I doubt that Renoir’s view would have been so optimistic. As it is, La Grande Illusion perfectly encapsulates the “liberté” and “fraternité” elements of French national motto: the “egalité remains illusory.

April 5, 2012 at 12:27 pm

Reblogged this on sumitta2012.