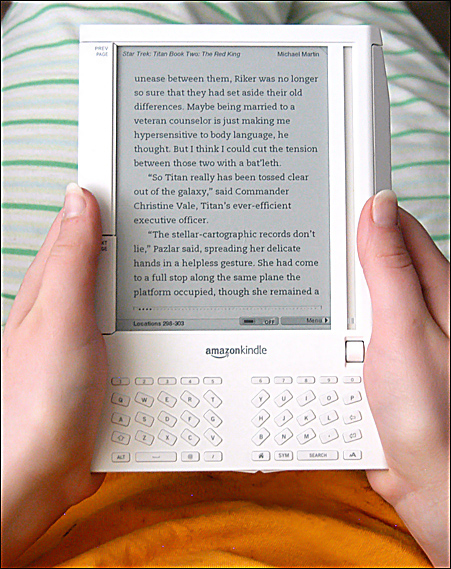

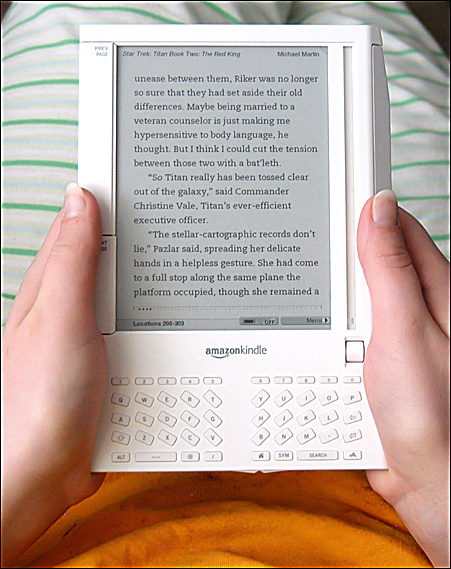

Another month; another sleek and seductive device arrives in shops. I can’t even get past Amazon’s home page without being smacked in the face by the breathtaking product shots of their “All-New Kindle”, which is modestly priced at £109 for the Wi-Fi version. OK, I may have exaggerated a little there, because the one in their picture does look like the dull, greyish and distinctly pedestrian cousin of Apple’s gleaming iPad. But who cares about the lack of sex appeal, when you can take your Kindle to the beach, or lounge around the bathroom enjoying that much-vaunted “Battery Life of One Month”.

Up until now I’ve been highly sceptical about the e-book revolution. I do love the convenience of my iPod with that cover flow display that puts all my favourite tunes right at my finger tips. But, as a bibliophile, I am still happy to settle for carrying around just one paperback book at a time. Not everyone shares my reverence for the printed word. Earlier this week, The London Evening Standard, ran a piece called “Living the iLife“, which promised to clue us in on what “today’s smart movers” were doing with their laptops.

The unfortunately named Mark Prigg describes the radical, stripped-down lifestyle of young, London-based entrepreneur Hermione Way. Apparently, she is one of the “digital minimalists” who are perfecting the art of living without clutter and running their lives from a selection of gadgets — MacBook, iPad, iPhone. She has already junked her CDs and DVDs and says “I’m in the process of chucking out all my books as I can read them on my iPad.”

To borrow what Urban Dictionary calls “an irritating piece of chatroom vernacular”, OMG! This woman is clearly one of those poor benighted souls who doesn’t appreciate the deep satisfaction of owning, living amongst and — yes, Guardian columnist Charlie Brooker — smelling books. You cannot enjoy a meaningful, lifelong relationship with a collection of digital files — no matter how good the contrast of the e-ink screen.

Then it dawned on me that Hermione might be right in thinking of books as something to read and then just throw away like yesterday’s newspaper. Of course they’re not exactly cheap — roughly £7.99 for the average paperback — but they feel less substantial. It’s partly a matter of perception: if you’ve grown up in the age of free cover mounts, or seen Dan Brown’s greatest hits piled high in supermarkets along with the baked beans and loo rolls, you could be forgiven for not regarding books as objects to treasure.

The decline of the book’s status has been compounded by deteriorating standards in editing, typesetting and printing. One of the reasons I now prefer second-hand books over new ones is that I believe I’m acquiring something with a bit of character. The slightly tanned pages and occasional bit of broken or misaligned type, make that old Penguin edition of The Great Gatsby unique. On the other hand, my 2007 paperback of Richard Ford’s novel The Lay of the Land runs to more than 700 pages and is printed on what the publisher boasts is “100 per cent post-consumer waste recycled paper”. Green it may be, but this book looks and feels like crap. To add insult to injury, the back cover is emblazoned with the usual hyperbolic nonsense from critics who, unlike me, were not defeated by Ford’s latest futile attempt at The Great American Novel.

Don’t even get me started on why hardback books should be so extortionately priced, just because they’ve been lazily glued together between a couple of pieces of board, with a badly designed jacket. Oh, and can anyone explain to me why the invention of the spellchecker now means that no-one ever feels the need to proof-read their work? I’m not charmed but infuriated by bestselling titles that have gone into multiple reprints still carrying the sort of basic errors that would shame a 10-year-old.

I’m not saying that my love affair with books is over: I won’t be abandoning my library any time soon. But for a certain kind of product — particularly newly published novels and biographies — I can see that there is now a viable alternative to rubbishy paperback editions that are riddled with errors. If the range of digital titles available is broad and prices are significantly cheaper than for the printed versions, then I don’t feel I’d be betraying my principles by joining the digital reading brigade.

Devices like the Kindle will make inroads into some areas of the literary market, but it certainly doesn’t mean the end for the book. While some kids will be lucky enough to get their sticky fingers on an iPad, others will still fall for the charms of the old-fashioned illustrated books their parents grew up with. I really can’t see how a single digital screen will suffice for students who are used to writing essays with half a dozen books spread open in front of them.

Kindle is a well-chosen name for a wireless reading device that claims to be so effective in bright sunlight. It may yet light a fire under the publishing industry as we know it and drive some e-zealots to start a few bonfires.

(Article first published as Burn After Reading: Embracing the E-book on Blogcritics.)

1 Pingback