When I watch The Servant, it's always the voice of Cleo Laine singing "All Gone" that echoes around my head for hours. John Dankworth's smoky torch song is as integral to Joseph Losey's haunting psychological drama as Barrett, the unctuous manservant played by Dirk Bogarde, or Harold Pinter's trenchant script.

Nearly 50 years after The Servant was first released, that combination of mellow voice, strings and lyrics filled with regret – "Leave it alone. It's all gone" – remains irresistible. For Tony, the hapless bachelor so brilliantly played by James Fox, it's the melodious accompaniment to his fireside lovemaking with Susan (Wendy Craig). By the end of the film it has turned into something horribly discordant – those stabbing strings mocking his decline into a life of booze and degradation, orchestrated by the manipulative Barrett. Tony can smash the record player, but he can't shut off the sound of his own destruction.

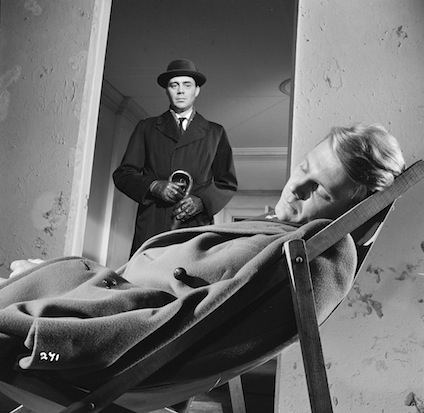

Though there's a lot more to The Servant than one song, it's a good indication of how everything we see (and hear) is perfectly calibrated by Losey, Pinter and their collaborators. From the moment Barrett first arrives at the terraced house just off the King's Road, Chelsea, those ticking and chiming clocks are hard to ignore. Like Douglas Slocombe's immaculate black and white photography, the timepieces contribute to the increasingly claustrophobic atmosphere. When you add the exaggerated sound of a dripping tap and Barrett's enormous shadow looming from the upper floors, The Servant would have made a great horror movie.

These days you'll find more polyglot nannies in Chelsea than bowler-hatted Barretts, but this dissection of the shifting balance of power between callow master and wily servant remains fascinating. Dirk Bogarde dominates proceedings, of course, even when he's offscreen. But it's a measure of his greatness that he doesn't completely overshadow the contributions of James Fox, Sarah Miles or Wendy Craig. The homoerotic subtext of the Tony/Barrett relationship has been much discussed, but there are only glimpses of camp when they squabble over domestic arrangements. The enduring power of this film lies in the fact that Barrett and his seductive "sister" Vera (played by Sarah Miles) remain unreadable and unknowable.

Far from being a sterile exercise in art house film-making, The Servant delights in sly humour – from the lingering shot of Thomas Crapper's sanitary ware emporium, to an absurd conversation about ponchos and capes. Made four years later, Accident also has its lighter moments, as Losey and Pinter examine hypocrisy and infidelity amongst a group of middle-class academics.

Accident was adapted by Pinter from the novel by Nicholas Mosley, and visually it is the antithesis of the earlier film. We've moved from austere, wintry west London to the glories of an Oxford summer – punting, cricket, tennis and Sunday lunches that last all day. Bogarde and Stanley Baker play a pair of middle-aged dons who share a mutual interest in a beautiful but vacuous Austrian student (played by the very French Jacqueline Sassard). Her other suitor William (Michael York), supplies the doomed upper-class element in a story that begins with a fatal car crash and then shows the betrayals that led up to it.

Accident is a dazzling and seductive piece of film-making that gives Bogarde another excellent role as the conflicted Philosophy tutor, Stephen. Married with two kids and another on the way, he appears simultaneously entrenched in and detached from his world of privilege and beauty. He's also frustratingly passive in the face of boorish behaviour by Baker's character, Charley. There's something theatrical about a film that locates many of its key moments – a birth, a violent death, illicit sex – offscreen. Like Stephen, the viewer is never quite in the right place at the right time, leaving many questions unanswered.

Unlike conventional romantic dramas, Accident doesn't move towards an emotionally satisfying resolution to the web of tangled relationships. Sequences like Stephen's meeting with old flame Francesca (Delphine Seyrig) don't unfold in the way you might expect. So instead of a conventional montage, scored with appropriate mood music, we get pictures and dialogue that are jarringly out of sync. Even more startling is a conversation between Stephen and his wife Rosalind (played by Pinter's wife Vivien Merchant) that takes place at the end of a long garden. When the reverse shot suddenly reveals that they're also sitting right next to a river, it's as though we've just cut to a completely different day and location.

Dirk Bogarde is far too cerebral to rank with mainstream 60s cultural icons like The Beatles, James Bond and Michael Caine. But the two emotionally complex films he made with Joseph Losey and Harold Pinter prove that style and substance weren't mutually exclusive in that "swinging" decade.