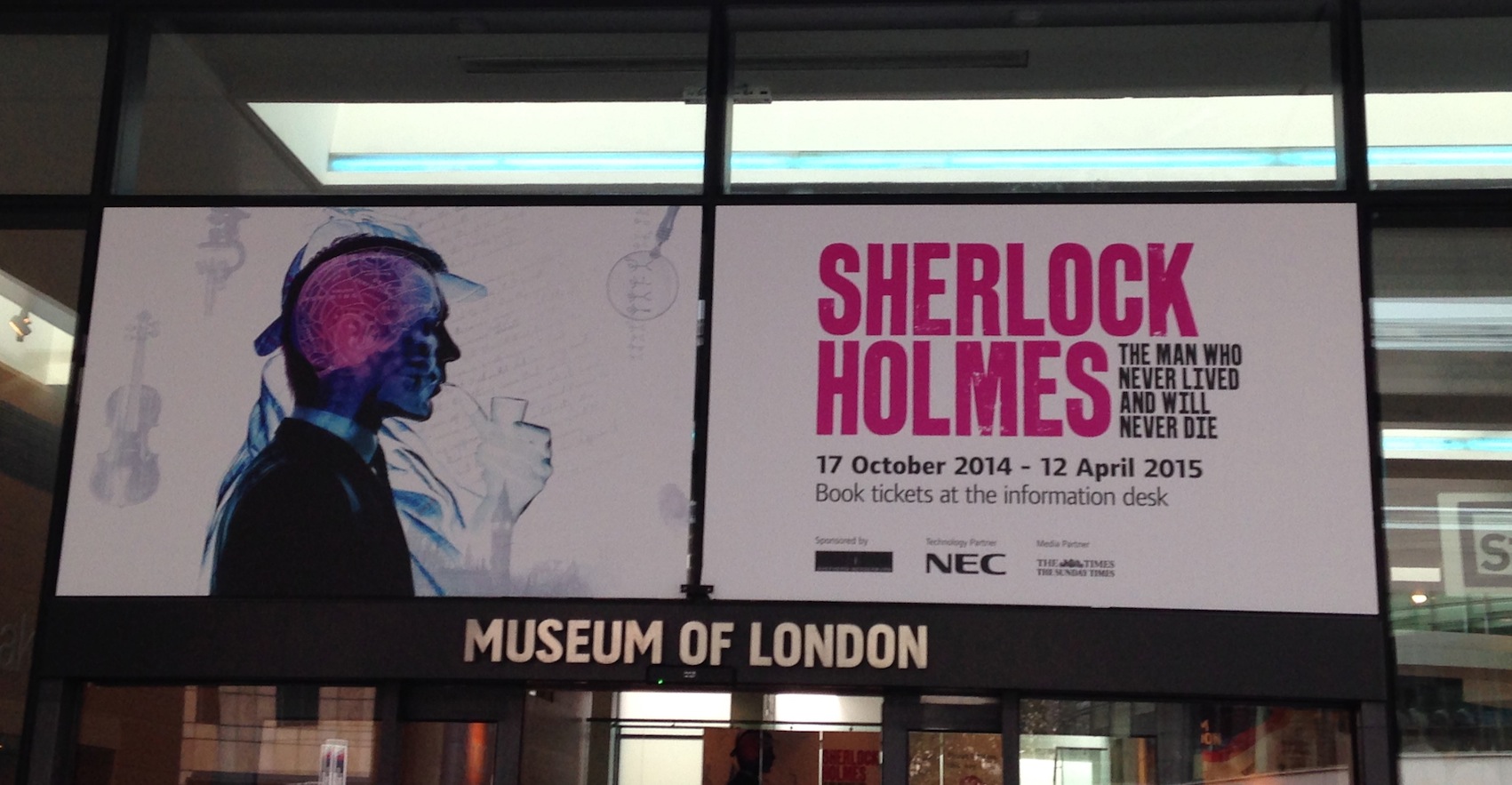

The Museum of London – a mid-70s hotchpotch of grubby concrete, white tiles and multi-level entrances – doesn’t look like the most obvious place to begin an excursion into the Victorian era. Hansom cabs being in short supply, I travelled to Sherlock Holmes: The Man Who Never Lived and Will Never Die on a shiny new Metropolitan Line tube. I changed trains at Baker Street (where else?). After descending two floors at the museum, I was directed “through the bookcase” into a world of gaslight, deerstalkers, dastardly villains and a consulting detective with superhuman intellectual powers and an unhealthy appetite for cocaine.

I discovered Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories a few Christmases ago and found them a welcome distraction from the bland landscape of seasonal telly. I’ve not seen much of the BBC’s Sherlock series because I prefer to watch the stories in their original (Victorian) setting. I’ll take the commanding presence of Jeremy Brett over the foppish Benedict Cumberbatch any day, but I know there are many fans who’d disagree.

In the first room of Sherlock Holmes: The Man Who Never Lived and Will Never Die the faces and voices of a century of screen Sherlocks crowd in on every side. William Gillette (who created the character on stage), Basil Rathbone, Christopher Lee, Tom Baker and Robert Downey Jr look down from banks of TV screens and walls of posters.

If you’re a film fan, your appetite will be well and truly whetted by the some of the posters advertising both “official” Sherlock Holmes movies and spin-offs such as the garishly shot A Study in Terror (1965). A slavering beast on Hammer’s superb Hound of the Baskervilles (1959) rubs shoulders with a busty femme fatale on the French poster from Billy Wilder’s 1970 The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes.

Fans of antiquarian books will enjoy seeing the beautifully illustrated and carefully preserved first editions of A Study in Scarlet. They’ll also discover a bit about the history of Tit-Bits magazine (note that hyphen) and its publisher George Newnes, who was the man behind The Strand Magazine.

If you’ve simply come to wallow in Sherlock Holmes memorabilia, you’ll have to go almost to the edge of the Reichenbach Falls to find it. In the penultimate room of the exhibition, fans can swoon over that Belstaff Milford coat worn with such panache by Benedict Cumberbatch. There are also cases of displays featuring everything from vintage typewriters, candlestick telephones, pipes and (cunning) disguises, to the fascinating accoutrements of the 19th-century cocaine addict.

But in between the posters and the artefacts, some visitors might be feel that they’ve strayed into a different exhibition. That’s because after introducing us to his creator Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (some of the author’s Southsea notebooks are on display), this show veers off into the streetscapes of Victorian London.

For those who like old maps, The Museum of London has meticulously plotted the course of some of Holmes’s most famous adventures, including A Study in Scarlet and The Hound of the Baskervilles. (In this pre-Google Maps era, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle apparently relied on the Post Office Directory to plan his indefatigable detective’s progress around town and the suburbs.)

Different colours highlight the routes takes by Sherlock Holmes and his sidekick Dr Watson, on foot, by train or their preferred mode of transport – a hansom cab. Underneath these maps, speeded-up video footage shows the same journeys through 21st-century London. What struck me was how boring and homogeneous the centre of the city looks today from the back of a speeding cab – a succession of Starbucks, Prêt à Mangers and mobile phone shops.

One of the five sections of Sherlock Holmes: The Man Who Never Lived and Will Never Die is given over to prints, etchings and paintings of London as it looked in Conan Doyle’s day. While these pictures don’t directly illustrate the stories they do give a flavour of the buildings, fashions and vehicles of this era of “pea-soupers”. Here you’ll find household names (Matisse, Whistler) cheek by jowl with many long-forgotten chroniclers of London’s lost landscapes.

In a different venue, the focus of this exhibition might have leaned more heavily towards the history of Sherlock Holmes on the big and small screen. At the Museum of London it is the inextricable links between the Victorian city and the adventures of Conan Doyle’s most celebrated character that take centre stage.