Prime Minister Harold Macmillan may have been thinking about The Titfield Thunderbolt when he made his often misquoted “never had it so good” speech in 1957. Released four years earlier, Ealing’s first colour film is an unabashed celebration of post-war optimism, community spirit, the glories of rural England, and the romance of the railways.

It’s the spring of 1952, and a notice goes up at Titfield station announcing that in a few weeks’ time British Rail will be closing the picturesque branch line to Mallingford Junction. This galvanises railway enthusiasts like the Reverend Sam Weech (George Relph) and squire Gordon Chesterford (John Gregson) into action. They apply to the Ministry of Transport to take over the running of the service, with funding from the bibulous Mr Valentine (Stanley Holloway), who’s seduced by the idea of a mobile bar. Lurking in the background are scaremongering hauliers Pearce and Crump, who plan to convert the village to the joys of bus travel – by fair means or foul.

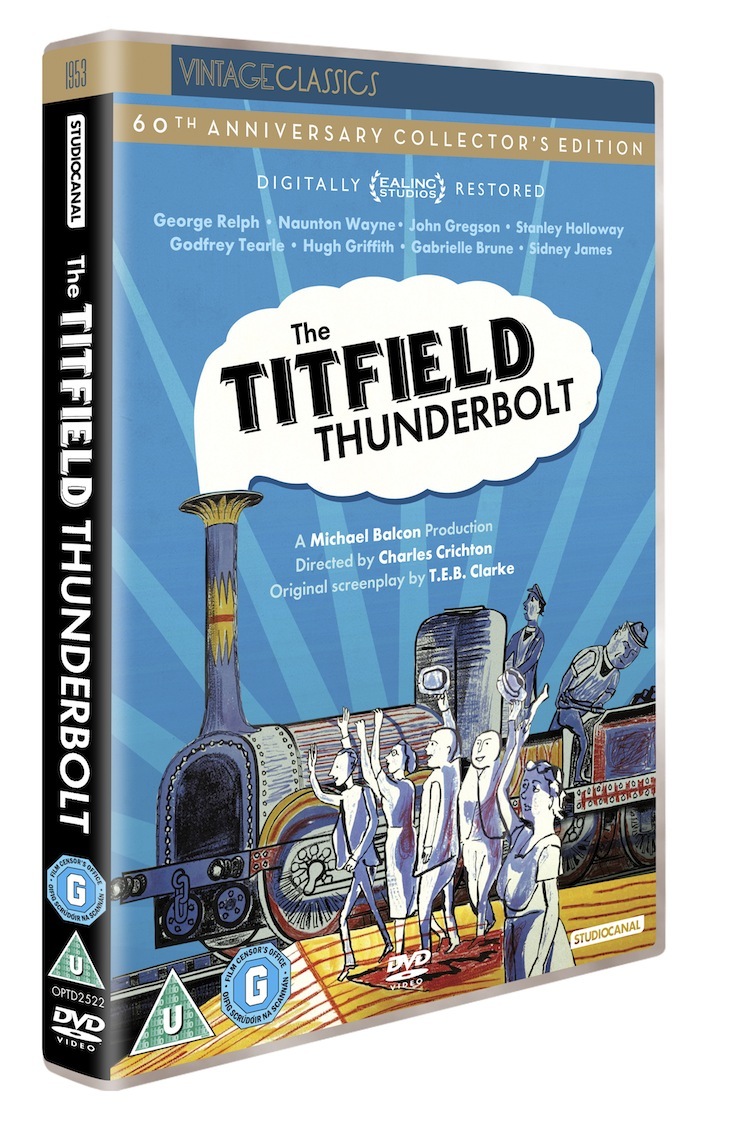

The Titfield Thunderbolt was directed by Charles Crichton and written by T.E.B. Clarke, who’d made The Lavender Hill Mob two years earlier. This 60th anniversary DVD release was the first time I’d watched the film, and I can confirm that Douglas Slocombe’s digitally restored cinematography looks lovely. Regular visitors to Bath will particularly enjoy watching the countryside of North East Somerset speed past, with starring roles for Monkton Combe station (standing in for Titfield) and the village of Freshfield.

It’s fun watching these light railway novices trying to outwit the scheming Crump (Jack MacGowran) and Pearce (Ewan Roberts), who’ll stop at nothing to derail the service. But the beginning of The Titfield Thunderbolt hints at what could have been an even better film, with a more satirical edge. Take the early scene in the pub, in which the amiable Weech almost comes to blows with railway veteran Dan Taylor (Hugh Griffith) over which man has the superior knowledge. “One doesn’t need a knowledge of working slang to operate a locomotive!” retorts Weech, in a sharply scripted demonstration of book knowledge versus hands-on experience.

Another key sequence sees the luxuriantly mustachioed man from the Ministry granting the villagers a one-month trial period to run the train. Trade unionist Coggett (Reginald Beckwith) launches a futile protest about the use of unpaid labour on the line, in tones reminiscent of Peter Sellers’s Fred Kite in I’m All Right Jack (1959). This proves to be story less concerned with politics than preserving the status quo in the decade before the first Beeching Report sounded the death knell for many railway lines. So it’s left to Jimmy Stewart look-alike John Gregson to give a barnstorming speech about how the end of the train service would condemn the village to death: “Our houses will have numbers instead of names!”

With no Alec Guinness in the cast, this Ealing comedy is very much an ensemble effort. George Relph probably has the most substantial role as the vicar-turned-driver, who switches between singing hymns and behaving like an excited kid let loose on a giant Hornby train set. A deadpan Hugh Griffith lets his pipe do the talking in their combative and eventful working relationship. Stanley Holloway always seems to get the last word as the permanently sozzled Valentine, and there’s strong support from Naunton Wayne and a pre-Carry On Sid James.

Fittingly, though, the real star of this film is The Titfield Thunderbolt herself (in real life the famous Lion locomotive), brought out of storage to save the day for the embattled train crew. Repainted for the film, Lion’s long career dates back to 1838 and lasted until the 1920s. These days Lion is a museum piece – on display at the Museum of Liverpool – and the same might be said about this colourful romp, championing the plucky volunteer spirit at the heart of the English countryside. Trainspotters will be in their element; fans of Ealing’s darker and more subversive films may be less enchanted.