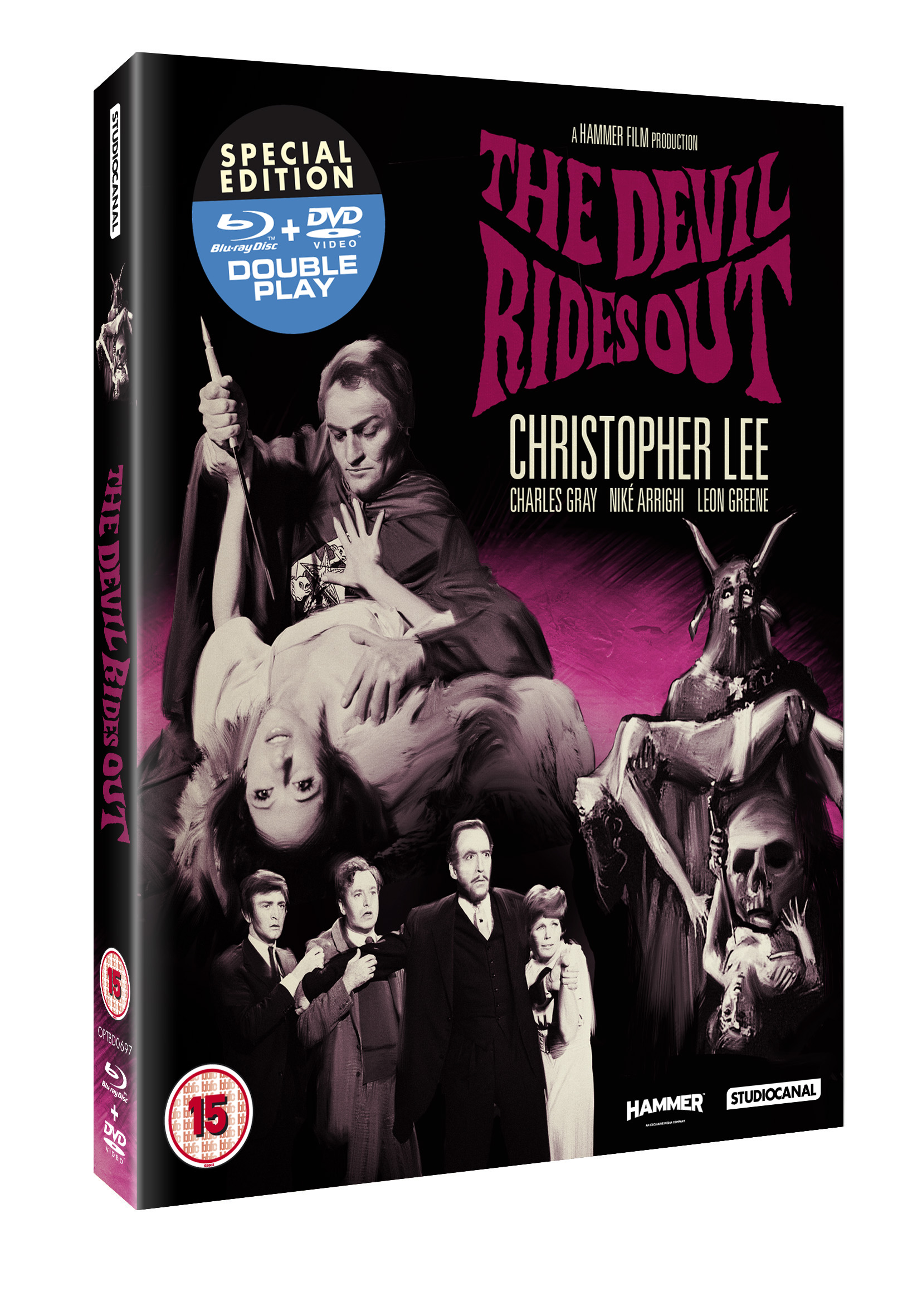

The Devil Rides Out (1968) is a fast-moving tale about devil worshippers in the leafy Home Counties, in which the actor best known as Count Dracula (Christopher Lee) goes head to head with the smooth-talker who once played Ernst Stavro Blofeld (Charles Gray). Arachnophobes may recoil at the restored version of the film’s celebrated giant spider sequence, but Lee fans will enjoy hearing him pit his expertise against Hammer historian Marcus Hearn on the film’s commentary track.

Against an elegant 1930s backdrop of sprawling country houses and veteran cars, satanists led by the powerful Mocata (Gray) are planning to initiate new member Simon Aron (Patrick Mower) into their circle of depravity. But the aristocratic Duc de Richleau (Lee) soon realises the true purpose of his ward’s “little astronomical society” and spends the next 90 minutes keeping Simon and Tanith (Niké Arrighi) out of Mocata’s clutches. Arming himself with salt and mercury — “effective against the dark forces” — the Duc’s formidable intellectual powers are seemingly unaffected by a lack of food or sleep. His sidekick Rex Van Ryn (Leon Greene, dubbed by Patrick Allen) provides some much-needed brawn, but is dangerously smitten with the lovely Tanith, through whom Mocata channels his powers.

The Devil Rides Out was adapted by Richard Matheson (I Am Legend) from a novel by Dennis Wheatley and directed by studio regular Terence Fisher (Dracula). With its tame (nudity free) orgy scenes and surprising lack of gore, The Devil Rides Out won’t raise too many eyebrows or hackles these days. We have Lee to thank for persuading producer Anthony Nelson Keys to greenlight the project, because despite the popularity of Wheatley’s books, it was still considered daring for Hammer to tackle a movie about satanism.

Lee will always be associated with his Hammer vampire roles, but he’s equally masterful here in a film that doesn’t require him to sink his teeth into anyone. While Rex handles the car chases and punch-ups, it’s always the Duc pulling the strings as he tersely issues orders and reveals the ghastly significance of finding a white hen and a black cockerel in a cupboard. He’s well matched by Gray’s smoothly understated performance as Mocata, in a part that some actors would have seen as an opportunity for unbridled scene chewing. The sequence in which he transfixes the Duc’s niece Marie (played by Sarah Lawson), is one of the most chillingly effective demonstrations of “mind over mind” ever committed to film. With his piercing blue eyes and perfect diction, Gray almost makes the triumph of evil seem like a victory for calm reason and good manners.

Sarah Lawson joins Christopher Lee and Marcus Hearn on a commentary track that isn’t quite as much fun as the one for Dracula Prince of Darkness. Lee, who knew Dennis Wheatley well, proves highly authoritative on the source novel and guides us through the terminology and ceremonies of the black arts. But he and Lawson obviously haven’t watched this film recently, and they have an annoying tendency to talk over each other. By the time we reach the climactic scene in Mocata’s basement, you wish they’d stop saying “I don’t remember that”, and that Lee wouldn’t keep droning on about the wonders of digital special effects.

The optical effects work of Michael Stainer-Hutchins on The Devil Rides Out is affectionately but honestly appraised by his son and daughter in one of the accompanying documentaries. Cineimage, who did the painstaking restoration work, explain how they cleaned up that gigantic hairy spider and the Angel of Death, without doing violence to the period nature of those effects.

The highlight of the extra features on this disc is the short appreciation of author Dennis Wheatley and his association with Hammer. His biographer Phil Baker has an uncanny and hilarious ability to dismiss the legacy of “Britain’s occult uncle”, while sounding terribly respectful. “One of the all-time great bad writers” he concludes, before conceding that the prolific author has now made the transition from being “merely dated to vintage”. It’s a description that could be applied to Hammer’s film adaptation of The Devil Rides Out, whose status as a genre classic is enhanced by this sparkling restoration.