This summer it looks as though the recipe for a great sporting event must include a soupcon of controversy, a hint of madness, a dash of celebrity and, of course, a Spanish winner. The World Cup gave us tuneless vuvuzelas, deliberate handballs and a goal that never was. Wimbledon played host to HM the Queen, David Beckham and an unfeasibly long first round match that lasted more than 11 hours. The 97th Tour de France featured several crashes, a head-butting incident, a little mechanical difficulty and a guest appearance from Tom Cruise and Cameron Diaz.

I’m ashamed to admit that cycling’s blue riband event rarely figures on my sporting radar. I’ve spent 30 years steering well clear of it, only half listening to news bulletins about the exploits of multiple winners like Bernard Hinault, Greg LeMond and Lance Armstrong. I live in London, where the local cyclists cruise the pavements like marauding bandits with a take no prisoners attitude, so watching the sport on TV seemed about as appealing as a dose of sun stroke.

But when I did finally tune in to the latter stages of this year’s Tour, I realised that personal prejudice, wilful ignorance of French geography and an unfamiliarity with team tactics wasn’t going to spoil my enjoyment. This was an event that had everything: from the compelling duel between Spain’s Alberto Contador and Luxembourg’s Andy Schleck for the coveted yellow jersey; to the scintillating speed of Britain’s top sprinter Mark Cavendish; and then there was the valedictory lap for 7-times winner Lance Armstrong.

If you like a little scenery along with some cut-throat competition, the 3,642 kilometres route from Rotterdam to Paris offers a wealth of highways, byways, châteaux and mountains. But for the teams, including Britain’s Sky, Armstrong’s quaintly named RadioShack and Denmark’s Saxo Bank, there are also numerous hazards that can leave you — quite literally — broken and battered by the wayside. One of the most striking elements for a Tour “newbie” like me, is just how dangerous it can be. Next time I see an overpaid footballer writhing in mock agony I’ll remember one-time race leader, Aussie Cadel Evans soldiering on with a fractured elbow that wrecked his chances on Stage 9.

Perhaps it’s an oversimplification, but there’s an element of that old fable about the tortoise and the hare in the respective journeys of Cavendish and Contador. Cavendish (HTC Columbia) won five stages this year, including the final stage along the Champs-Elysees, but lost his bid for the green jersey to Italy’s Alessandro Petacchi. Despite his blistering speed, he finished 154th in the overall standings, whereas Contador failed to win an individual stage yet finished nearly four hours ahead of the Brit.

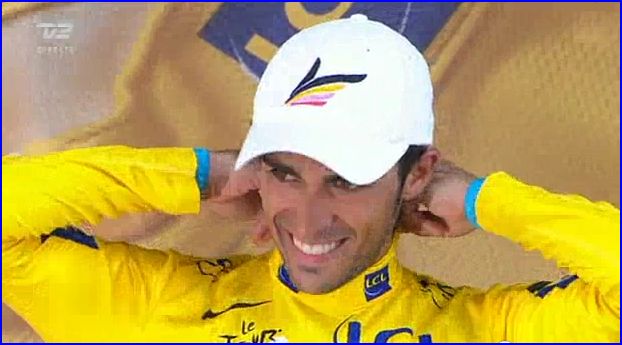

Was the Spaniard’s narrow 39-second victory against Andy Schleck — his third overall win — a result of greater guile and experience, or his willingness to take advantage of his rival’s misfortune? During my limited exposure to the Tour’s history I seem to have heard a lot of stories about doping, disqualifications and strenuous denials. When Schleck faltered after slipping his chain on the climb up the Port de Bales in the Pyrenees on Stage 15, Contador passed him, eventually claiming the yellow jersey. The condemnation from the commentators and spectators was long and loud.

There’s so much cheating now in professional sport, I found it surprising and somehow old-fashioned to hear people talking about “fair play”. Apparently it’s considered a breach of cycling etiquette if you turn cartwheels and go zooming ahead when your rival runs into problems. Still, only days before, Cavendish’s team-mate Mark Renshaw had been thrown out of the Tour for his decidedly ungentlemanly head-butting of Julian Dean.

In the aftermath of this misfortune, the smiling Schleck reminded me a lot of Judge Reinhold in the movie Fast Times at Ridgemont High — a likeable, boyish figure, somewhat peeved at the failure of others to live up to his high standards. His vow of “revenge” led to a thrilling game of cat and mouse with Contador during the 17th Stage, on the gruelling ascent of the Col du Tourmalet. They were locked in combat, wheel-to-wheel, eyeballing each other furiously, with the watchful Contador content to let Schleck make the running to try and claw back those lost seconds he needed. Schleck won that battle but lost the war.

It was watching those fog-shrouded scenes on the Col du Tourmalet that made me realise this was a sport I could really get excited about. Most sports take place in hermetically sealed, purpose-designed stadia, but this one invites spectators the length and breadth of the country to get up close and personal with the riders. Some of these people are clearly mad.

There were exhibitionists of all shapes and sizes on that narrow mountain road, some “mooning” the cameras, others sporting Borat-style mankinis and many brandishing flags that threatened to knock the riders off their cycles. As some Spanish fans tried to run alongside Contador, I realised that these displays of deranged machismo wouldn’t have been out of place during the Pamplona Bull run. Viva Espana!

(Article first published as Chain Reaction: The Climax Of The Tour de France on Blogcritics.)