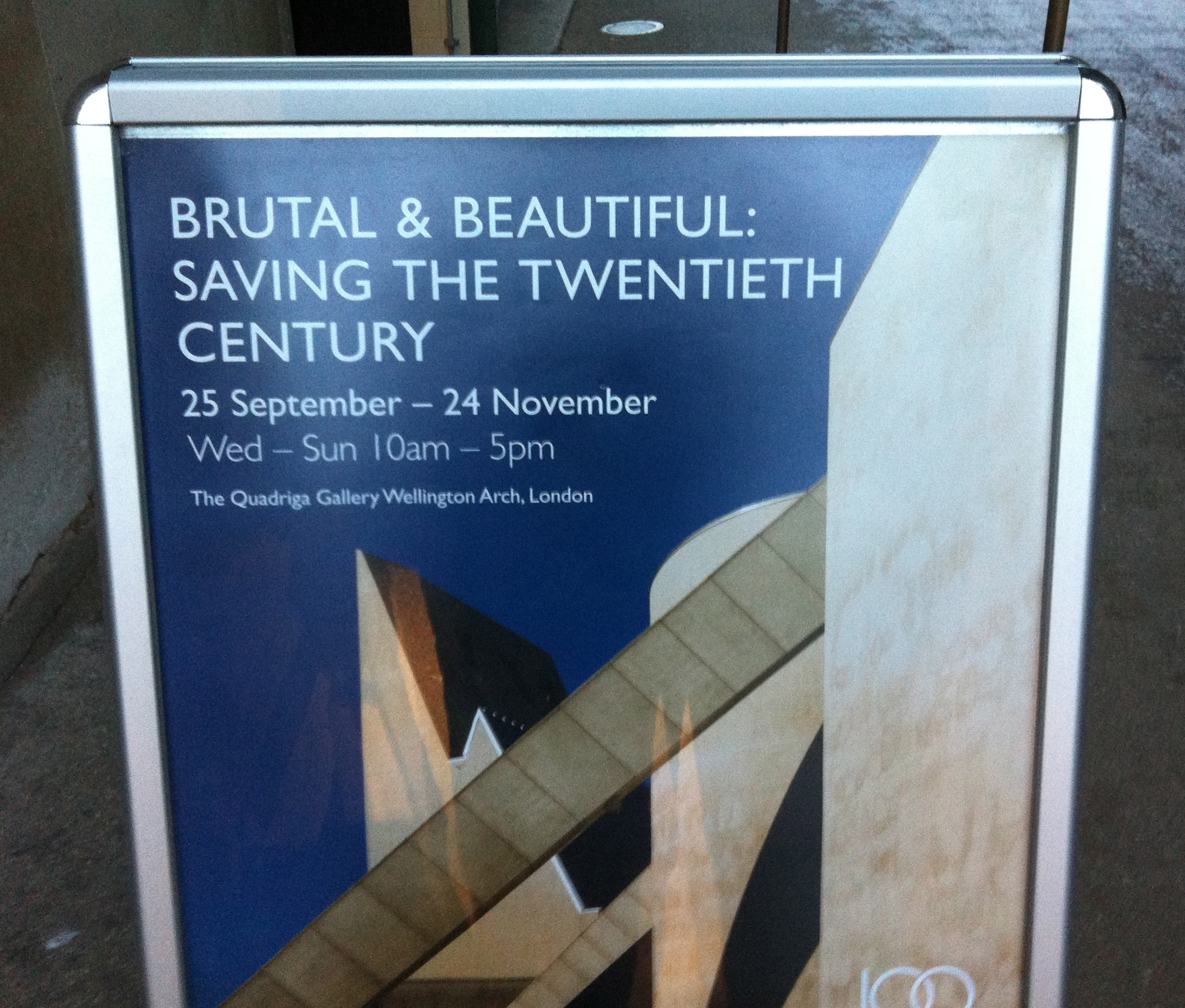

London has many museums, but until last week I didn’t realise there was one slap-bang in the middle of Hyde Park Corner. The elegant classical proportions of the Wellington Arch belie the Tardis-like properties of this overlooked landmark. Inside you’ll find the Quadriga Gallery, which is currently hosting English Heritage’s “Brutal & Beautiful” exhibition.

If you’ve seen the BBC4 series, Heritage! The Battle for Britain’s Past, you’ll already know that this year is the centenary of the 1913 Ancient Monuments Act – the point at which compulsory preservation orders and the “scheduling” of important national monuments came into effect. But you won’t find anything “ancient” in this exhibition, which covers a more recent period in the nation’s ongoing struggle to decide which parts of our rich and varied architectural heritage are worth preserving.

I expected a review of listed buildings since the Second World War to spend a lot of time focusing on concrete. Like many people I have a love/hate relationship with this most unloved of building materials. When I think of 1960s architecture in Britain I find it hard to get past images of ugly shopping centres and Owen Luder’s Gateshead car park (now demolished), which achieved cinematic immortality in the film Get Carter. But I have grown to love London’s Barbican Centre and housing complex – a concrete jungle alleviated by gardens, balconies and my favourite waterside terrace in the City.

“Brutal & Beautiful” does include a striking photo of the Barbican’s Cromwell Tower – flaunting its distinctive “upswept balconies” as it soars into a clear (and perhaps digitally enhanced) blue sky. But there are other late 20th-century buildings here that don’t smack you round the head with their “brutalist” credentials. There’s Sir Denys Lasdun’s Royal College of Physicians, which is described on the RCP’s own website as a “modernist masterpiece”. I’ve never been there, but with its Marble Hall and oak panelling (transferred from an earlier RCP building), it looks like the perfect marriage of light and dark, classical and modern.

I haven’t visited Coventry either, but if anything was going to lure me to that corner of the West Midlands it would be Sir Basil Spence’s Cathedral, which features stained glass windows by John Piper and tapestry by Graham Sutherland. Can anything modern possibly rival the magnificence of those Gothic cathedrals that were lucky enough to avoid a direct hit from the Luftwaffe? Well the new Coventry Cathedral is Grade I listed, so its position as an icon of 20th-century ecclesiastical architecture is secure.

On a smaller scale, “Brutal & Beautiful” highlights some lovely examples of domestic architecture that will excite fans of mid-century modernism and cool Scandinavian interiors. I particularly liked the look of Peter Womersley’s Farnley Hey, in West Yorkshire. I’ve just found this listing, which values this four-bedroom “American contemporary style” house, with its floor-to-ceiling windows, at just £575,000.

If I could, I’d buy Farnley Hey and have its York stone flags and camphorwood interiors transported to the overpriced corner of west London where I currently reside. Unfortunately it wasn’t built to be moved – unlike the revolutionary pre-fab homes featured elsewhere in this exhibition.

Even better are the cluster of three houses at Turn End in Buckinghamshire, which feature in one of the exhibition’s three short films. Architect Peter Aldington created this mini-development in the 60s, with his wife Margaret and they still live in The Turn, where garden and living space seem to blend seamlessly into one. It looks magical – a reminder that great modern buildings have character, soul and are fit for purpose.

“Brutal & Beautiful: Saving the Twentieth Century” continues at the Quadriga Gallery, Wellington Arch until 24 November.