The day after 94-year-old Kirk Douglas tottered onstage at the Oscars, Hollywood lost another of its golden greats in the shapely person of Jane Russell. The coverage of her death has (predictably) focused on that famous cleavage and the somewhat surprising news that Russell was a Republican. Right-wingers in Tinseltown always seem to attract an undue amount of opprobrium, so let’s cut her some slack. After all, she was a movie star, a singer and sex symbol — not the Governor of Alaska.

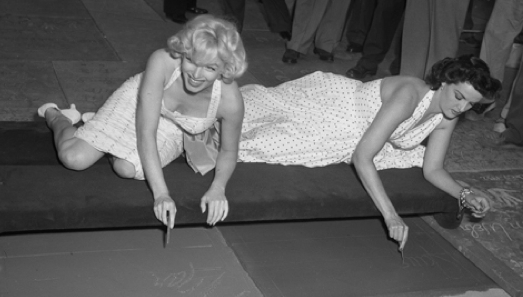

If you wanted to explain the essence of 50s Hollywood glamour to a visiting alien, you could do worse than to run the opening sequence of Howard Hawks’s musical Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. As Jane Russell and Marilyn Monroe sashay on stage in their red sequins and feathers, singing “Two Little Girls from Little Rock”, the impact remains startling even today.

Blondes isn’t the best film Monroe or director Howard Hawks ever made, but as an example of sheer star wattage it is hard to beat. Everyone remembers Marilyn’s Lorelei Lee clad in pink and singing about her love of diamonds, but Russell’s Dorothy has her own show-stopper with the (retrospectively) camp “Anyone Here for Love?”. Perhaps the current Hollywood obsession with the colour “nude” began with the tiny shorts Jane’s musclebound co-stars are sporting in that scene. She also gets some of the best lines, managing to gently deflate her co-star without ever appearing bitchy. How many other actresses could have shared a screen with Marilyn in her prime and not be rendered invisible?

Ernestine Jane Geraldine Russell was originally from Minnesota, but later moved to Southern California where she grew up on a ranch with her four brothers. In 1940 she attracted the attention of Howard Hughes — always a connoisseur of female pulchritude — which led to her being cast in the western The Outlaw. If you’ve seen Martin Scorsese’s The Aviator, you’ll know that the delicate issue of Russell’s décolletage was quite a big deal at the time. She was famous — or infamous — long before the movie ever saw the light of day.

As the hyperventilating trailer suggests, The Outlaw isn’t exactly the definitive take on the story of Pat Garrett and Billy Kid, but who cares? This was Jane Russell’s screen debut and the impact of her raw sexual magnetism was enormous. Her acting skills may have been limited, but then so were Lauren Bacall’s in the equally memorable To Have and Have Not. Whatever you think of Hughes’s artistic credibility, or lack of it, he knew how to make his new leading lady’s assets count — at the box office.

Russell’s career on the big screen was, to be honest, rather patchy. Despite her spectacular looks, a decent voice and a flair for comedy, she didn’t emulate Monroe’s success in working with some distinguished directors. Her films with Bob Hope, The Paleface (1948) and Son of Paleface (1952) are still fondly remembered and in 1951 she was paired with Robert Mitchum in the minor noir, His Kind of Woman. For RKO Studios this was, as Mitchum’s biographer neatly puts it “The screen’s two greatest chests, together for the first time.”

Russell was married three times, most famously to quarterback Bob Waterfield from 1943-1967. Unable to have children, she adopted three and founded World Adoption International Fund, which rejoices in the acronym WAIF. Arguably, helping to find homes for unwanted kids is a much greater contribution to humanity than making movies — good, bad or indifferent. But I suspect Jane Russell is going to be remembered for her humour, her longevity and the indelible impression she leaves as one of Playtex’s most famous models.