If you’ve watched enough Hollywood films, you’ll already know that the 1960s were just one long drug-fuelled odyssey, with semi-improvised plotlines, gratuitous nudity and great music. For those who weren’t lucky enough to be tuning on or dropping out in Southern California or Swinging London, the glittering coastline of the Côte d’Azur must have been a pretty good third choice. But in Jacques Deray’s La Piscine (1969), a month of R&R in the South of France climaxes in death, disillusionment and the inescapable feeling that the party is over.

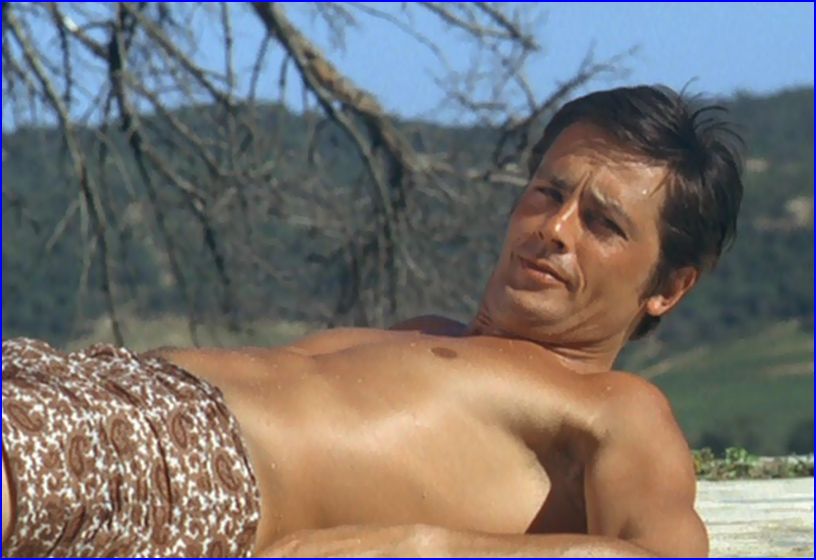

Tanned, toned and utterly carefree, Jean-Paul (Alain Delon) and his girlfriend Marianne (Romy Schneider) frolic in and out of the pool at their borrowed holiday villa near St Tropez. With no kids and no guests to entertain, there’s nothing to do except make love, sleep late and wait for the next meal to be served up by their obliging maid. Then Marianne learns that her old friend Harry (Maurice Ronet) is in the neighbourhood with his daughter. Without consulting her partner, she invites them both to stay. Tensions rise as Harry rolls up in his Maserati with leggy 18-year-old Penelope (Jane Birkin) in tow. The sun beats down as Jean-Paul alternates between sulking and smouldering; Marianne is seemingly oblivious to the consequences of her hospitable gesture.

I first watched La Piscine in a state of mild intoxication, which was ideal for enjoying a story about shallow hedonists summering in the playground of the rich and famous. There’s not too much dialogue here to interrupt your appreciation of those lingering shots of Delon’s glistening torso as he hauls himself out of the pool, or the camera’s relentless quest to shoot Romy’s dazzling beauty from every conceivable angle.

But on second viewing you realise that the languid pace and luscious photography have lured the audience into the same false sense of security as Marianne. The screenplay, co-written by Deray and Jean-Claude Carrière, subtly draws out the fault-lines in the relationships between the central trio. Harry, who favours tailored shirts worn unbuttoned to the waist, initially presents himself as genial, successful and popular with everyone he meets. Yet he can’t resist needling the younger Jean-Paul at every opportunity – quizzing him about his half-hearted new career in advertising, Marianne’s work and their future. His relationship with Penelope (“a mistake of my youth”) is a sham that simultaneously fuels his anxiety about getting old while playing to his vanity.

In other words, it’s the classic scenario of two alpha males locking horns over the same woman, with Jean-Pierre initially unaware that Harry and Marianne were once lovers. He’s reduced to shooting baleful glances at the pair, as they cosy up to each other during a party scene. He consoles the ingénue Penelope, who has earlier observed at close quarters her father’s lustful gaze at the bikini-clad Marianne. No dialogue is really necessary to convey the simmering jealousy and pent-up rage that will drive Jean-Pierre to seduce Penelope and strike out at his tormentor.

A lesser actor than Maurice Ronet might have turned Harry into the kind of preening braggart you’d quite happily see floating in your pool. But I still found Harry oddly likeable even when he’s being boorish. When he drowns, it feels for a while as though the life has been sucked out of the film and the increasingly fragile relationship between Marianne and Jean-Paul.

Despite Jean-Paul’s ham-fisted efforts to tamper with the crime scene and a suspicious detective from Marseilles, La Piscine remains a psychological drama rather than a thriller. So the final third of the film focuses on Marianne’s slow realisation that her lover’s weaknesses and failures go far deeper than she ever imagined.

This is where Delon and Schneider, who had once been engaged for five years, show that there’s much more to their performances than just modelling beachwear around the swimming pool. The scene in which he announces he’s leaving her is a masterpiece of understatement and barely articulated regret, complemented by the piano and violin on Michel Legrand’s hauntingly beautiful score. There are no histrionics here: the look of utter devastation on Schneider’s face as she returns to their bedroom alone says it all.

That’s not the end, though. As an autumnal chill blows through the Riviera, La Piscine reunites this glamorous pair for a future that looks to be full of compromises, uncertainties and – perhaps – a genuine commitment this time.